Wyrd biþ swiþre, Meotud meahtigra, þonne ænges monnes gehygd.

Fate is stronger, the Lord mightier, than any man's thoughts.

This is part two in a series of posts on some Old English poetry from the 10th-century Exeter Book. I will likely return to this series between other posts in the next few months. Thank you for all the feedback on part one, which you can find here if you missed it:

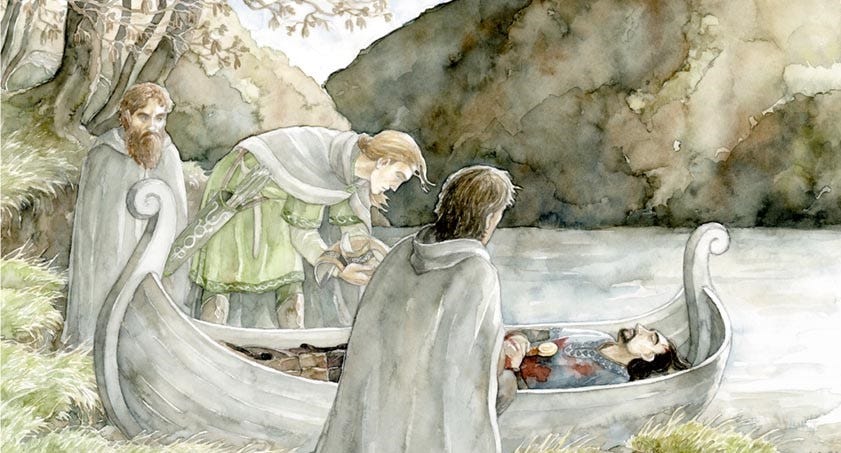

This poem has had a significant impact on English literature. Others have undertaken more scholarly examinations of The Seafarer, and this post will simply be appreciating its wisdom.1 The poet Ezra Pound has a famous loose translation of the poem’s first half that can be found here. J.R.R. Tolkien undoubtedly knew this poem, along with The Wanderer, and its influence can be seen in LOTR.2 I am once again using Michael J. Alexander’s translation found in The Earliest English Poems. I have here attached a PDF containing his translation here.

The first half of The Seafarer recounts a man’s life of trial. Trial is the wrong word, it is too close to the Latin terra; its feet are too planted. Sorrow is better. It tells how he has, “wasted whole winters… cut off from kind.” In the second half the man reflects on the loss of good men in his day, the futility of riches, the reality of an approaching eternity, and the wisdom his hardships have brought him. He then finishes with a doxology.

One Must Steer a Strong Mind

Stieran mon sceal strongum mode, ond þæt on staþelum healdan.

One must steer a strong mind, and keep it steady.

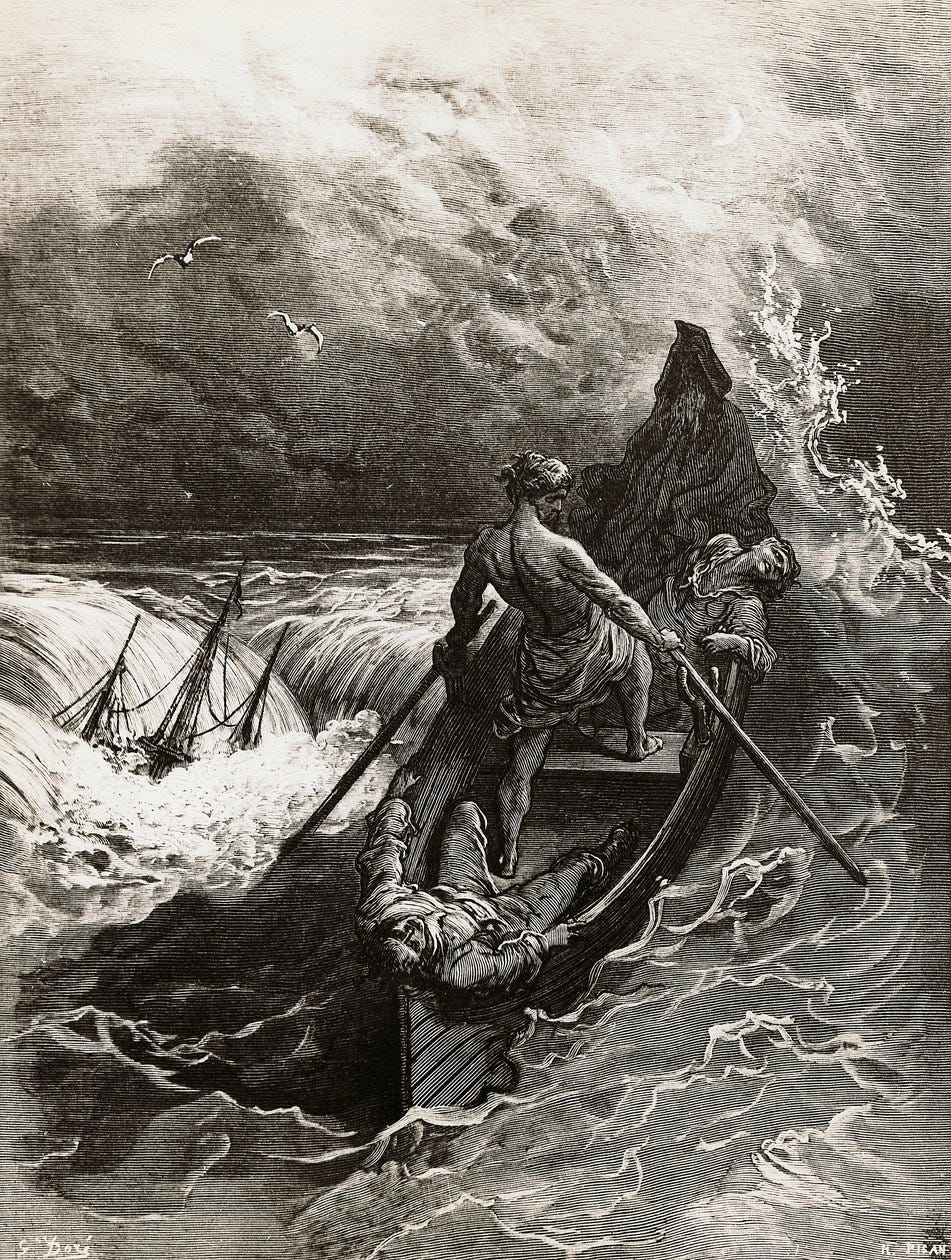

I find it amazing that we can pick up this poem from a thousand years ago and see the same internal battles of the mind underway. This quote is one that I think all men can understand. One must steer a strong mind, and keep it steady. Alexander’s translation renders it, “A man should manage a head-strong spirit and keep it in its place.” This is the battle of the Christian man. To be a man is to have the waves of life hit your boat, and to stay the course. Strength of mind is not an optional virtue to develop:

Not only that, but we rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance…(Romans 5:3)

I think some of that sentiment is expressed by reading older literature, whether it be fiction, nonfiction, or poetry. You see an acknowledgment of suffering, but without excessive self-pity or complaining. One of the Anglo-Saxon virtues is wærwyrde, “wary with words”. We should not throw up a spray of pity with our words when life is hard.

There are ditches on both sides of the road: keep everything in until you resort to sinful outlets, or perform the exhibitionism that the feminized zeitgeist preaches: “talk about your emotions.” I like the path that older wisdom literature took. Admit that life sometimes hits you hard in the chin. Tell it like it is. Write an epic poem about it if you want. But pray to God and pull the oars again. In these older works of literature, you see men to whom no earthly help came, and they had to endure. And enduring suffering is often its own victory.

A Man’s Despairing Mind

No friend or brother by to speak with the despairing mind.

The worst aspect of any man’s suffering is facing it alone. I do not mean literally alone in the sense of proximity to other humans, although that is sometimes part of it. But I mean an internal loneliness, where the depth of your suffering is known to you, and you alone. When your eyes are the only ones that see your hands gripping the oars, pulling, and pulling, and pulling. When your fingers are the only ones aching.

The heart knows its own bitterness (Proverbs 14:10)

Each of our hardships can be very different. Sometimes people despair that no one understands their specific concoction of suffering. But God knows all of our sufferings, and our suffering is common enough for Christ. What I mean is that Christ can sympathize with our weakness, in that He became man, like unto us in every way with the exception of sin. He knows your suffering because He suffered.

So we are not to feel entitled to the pity of others, because we are not owed it. Feeling entitled to pity is a short step away from bitterness, which is a short step away from the envious pride by which Satan fell. We can do all things through Christ, be it abundance or lack. But it is significant that a man who was in political exile as the Seafarer was should mention “no friend or brother by to speak with the despairing mind” in his list of hardships.

Be Christ’s hands and feet to your brother who is suffering. If a man can open his “despairing heart” to you, you have given him something that money cannot buy. It is an invaluable gift. It is better to shut up and say nothing rather than to be a Job’s comforter. But, if you can be a godly friend to that man in suffering, you are heaven sent help. You are as an ambassador of God to him, binding up and loosening those sufferings; you are bailing water as he is rowing.3

Wyrd Waters

The Odyssey. The Iliad. The Aeneid. Treasure Island, Moby Dick, Heart of Darkness, The Old Man and the Sea. Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The maritime analogy is a powerful one to describe the experience of manhood. The sea is a picture of wisdom-producing hardships in many important works of literature and in the Sacred Scriptures themselves.

In Genesis, we have God separating water from water4 in creation, bringing order. We have Noah’s flood in which God destroyed a world of unrighteousness, but saved those who believed. In Exodus we have God delivering His people and destroying His enemies. He has triumphed gloriously, horse and rider he has thrown into the Sea.5

We see God’s judgement and we see God’s kindness. We see His salvation, and we see his justice. We see a wave touch the shore and remember that “righteousness and peace kiss.”6 Water is beautiful; it is terrible. It is good, it is severe. The disciples are crying out, “We are going to die!”7 and the Lord is sound asleep below the deck. Life is often like that. We look at Noah’s flood: what tumultuous times! They were times of judgement. But they were also times of deliverance. The storms of life often bring us terrible, necessary water.

A man may have to take a long voyage in long winters. His job may be horrible. His family life may be rough. He may have health complications. That can be mentally taxing in a way some people will not understand. The “land-dweller can't know”, as the Seafarer says.

But the Lord knows. He knows His own, and His own know Him.8 And He is with the Seafarer when he passes through the waters.

When you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and when you pass through the rivers, they will not sweep over you. (Isaiah 43:2)

Sometimes manhood is going to be rowing alone on cold waters, chin toward God. Rowing alone, because both oars are in your hands, and there is neither friend or brother who can pull them for you. Rowing even when you feel fear, for no man is so thoroughly equipped or strong

that before fairing on the sea he does not fear a little whether the Lord shall lead him in the end.

Rowing in secret, but your Father who sees in secret will reward you. Rowing alone, yet not alone.

Yet I am not alone, for my Father is with me. (John 16:32)

Gold & Fame in Death

Gold hoarded when he here lived cannot ally the anger of God toward a soul sin-freighted.

This is how the poetic portion of The Seafarer ends. As with the ending of The Wanderer, the poem ends with an admonition to value God’s forgiveness as our greatest possession. These men knew that the forgiveness of the Father is more valuable than the gold of all the feasting halls in all Wessex.

Earlier in the poem, the Seafarer talks about the futility of a man burying his brother with golden treasures strewn over his dead body. In our day, it is not common for people to think that a lavish funeral means a good afterlife. But in the days of the Seafarer, with the pagan years still in memory, that would have been a temptation.

But our own secular attitude to death is almost worse. They had wrong thoughts about death, but we have no thoughts about it. We have very simple, understated funerals, but we spend our entire lives in materialism, trying to distract ourselves from death. If the ancients were sometimes overly superstitious, we are willfully blind to our mortality.

In both cases, man is trying to use wealth to escape the sting of death: the ancients with wealth in death, the modern man with wealth in life. But what is the sting of death?

The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law… (1 Corinthians 15:56)

Death’s sting is sin. It is not poverty. It is not being forgotten by your successors. It is sin, and its power: the perfect law of God. Can money pay off the law of God?

For the Lord your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome, who is not partial and takes no bribe (Deuteronomy 8:17)

God takes no bribe. The law cannot be fulfilled with your gold, in life or in death. Only the Son, who fulfilled the Law perfectly, can take that sting away.9

Your gold means nothing to God. It does not matter what your annual income is: you do not make enough to pay the price of sin. If you are dirt poor but your sins are forgiven, you are richer than all the Fortune 500 CEO’s put together. The Seafarer closes with a prose section: a doxology praising the great power of God. It contains this reminder:

Foolish is the man who does not fear his Lord; death shall come upon him unprepared. Blessed is the man who lives in trust; grace shall come to him from the heavens.

In Alexander’s introduction to The Seafarer, he talks about how the traditional pagan way to overcome mortality for a man was earning fame ‘before wayfaring’ from heroic deeds. The Seafarer is not alien to this idea, but, as with the warrior virtues of The Wanderer, this pagan idea has found its fulillment in Christ. This Anglo-Saxon has been baptized into Christ, and the “deeds this time are against the devil, and the fame is among angels.”

[fame] won in the world before wayfaring, forged, framed here, in the face of enmity, in the devil's spite: deeds achievements. That after-speakers should respect the name and after them angels have honour toward it for always and ever. From those everlasting joys the daring shall not die.

May we do the works that spite the devil. The works that win fame amoung righteous men and angels. The servants of Jesus Christ overcome all the powers of the evil one by thier faith. God has prepared these good and glorious works for us to walk in.10 Many Christians righly reject selfish ambition. But we are commanded to have a godly ambition: not that we earn this by our merit, but that we press on to make that glory our own, becasue Christ has made us His own. We are commanded to seek fame and glory before the right Audience.11 May we seek glory: not the glory that comes from man, but the glory that comes from the only God.12

…to those who by patience in well-doing seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life (Romans 2:7)

O Lord, in thee have I trusted; let me never be confounded.

If no citation is provided, quotations are from the text of The Seafarer as found in The Earliest English Poems translated by Michael Alexander, or from the incredible work done by Clerk of Oxford here.

See this article exploring some of the passages in The Lord of the Rings directly influenced by The Seafarer.

I aim to write a future post on friendship and hardship digging into these ideas further.

Genesis 1:7

Exodus 15:1

Psalm 85:10

Mark 4:38

John 10:14

Romans 8:2-4

Ephesians 2:10

A Defence of Pride for more on this concept.

John 5:44

My friend, this was an absolutely incredible article.

In the last month, I actually re-read Moby Dick - then the book of Jonah - then a couple of other famous "seafaring" stories from across history.

So personally, this article really could not have come at a better time. But as always, you explore such incredible depths here.

From much of my past, I relate so strongly to the feeling of loneliness and "rowing alone".

But also, nowadays - to striving to be the kind of man who offers others the space to "open their despairing heart".

Really incredible work. Thank you.

Sirach 38:16–23

“My son, shed tears for the dead; raise a lament for your grievous loss. Shroud his body with proper ceremony, and do not neglect his burial. With bitter weeping and passionate lament make your mourning worthy of him. Mourn for a few days as propriety demands, and then take comfort for your grief. For grief may lead to death, and a sorrowful heart saps the strength. When a man is taken away, suffering is over, but to live on in poverty goes against the grain. Do not abandon yourself to grief; put it from you and think of your own end. Never forget! there is no return; you cannot help him and can only injure yourself. Remember that his fate will also be yours: ‘Mine today and yours tomorrow.’ When the dead is at rest, let his memory rest too; take comfort as soon as he has breathed his last.”