It is not easy to get anyone excited about reading obscure, esoteric, thousand-year-old literature in the first place. It is even harder to do it in a newsletter email. But I hope that my readers will appreciate my recommendation in this post. I prefer to tell people about ancient esoteric literature in person: where I can use lots of hand motions and storytelling to either draw them in as a willing initiate or to alienate them completely. Doing this in person has a much higher success rate than doing it in an essay. But hopefully, this will propagandize some of you.

Or at the very least, I hope this will sit in your memory until the next time that you see this esoteric work of literature mentioned, and you say to yourself, “Oh, that guy was not completely crazy, there are other people who know what this is also!” and then you will read it.

The Wanderer

Either way, this is your invitation to read The Wanderer, an Old English Poem at least as old as the 10th century. It is about a wandering Anglo-Saxon man who is reminiscing about his youth. He contemplates the good old days of feasting, fighting, and friendship with his boys. It is an echo of the wisdom expressed in Ecclesiastes. This poem is recorded for us in the Exeter Book, an important manuscript forming the foundation of English Literature.

I have the poem in print in The Earliest English Poems, skillfully translated from the unintelligible Old English by Michael Alexander. I highly recommend picking this book up: there are many excellent poems in it including the Battle of Maldon, an influential work for Tolkien, and Alexander’s translation brings the alliteration of the original texts through very well. If you like Tolkein, if you like Lewis, if you like laconic sayings, if you like the Iliad, if you like the Odyssey, then you will like these poems. The ancient world produced a very different type of poetry than what you can find today.

I have prepared a PDF of The Wanderer here1:

Baptized Old Anglo-Saxon Blues

The Wanderer occupies a unique cultural moment. Scholars think it is from the late 10th century, but could be older. It presents us with the picture of an Anglo-Saxon whose pagan history is still a recent memory. The Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity around the 7th century, so their clothes were still dripping wet with the waters of Holy Baptism when The Wanderer was written.

And, to make the poem cooler, you are listening to the Wanderer tell a story about his younger days. You get him singing the blues. You get to hear a traveling warrior from ancient, wild Anglo-lands, who talks to you about what it is to be a man, to suffer, to rejoice, and to believe in the God of gods.

Before getting to the actual wisdom in the poem, I want to make an observation about culture. “Culture” includes the wisdom literature of that people group. Chesterton has noted that philosophy and religion in paganism were often two distinct streams, not necessarily the same river2. We can reject the river of the pagan cults, and still see that there are good truths in the stream of Philosophy or wisdom literature in a pagan culture. Clement of Alexandria called Philosophy the handmaid of Theology:

Thy foot will not stumble, if thou refer what is good, whether belonging to the Greeks or to us, to Providence. For God is the cause of all good things; but of some primarily, as of the Old and the New Testament; and of others by consequence, as philosophy… Philosophy, therefore, was a preparation, paving the way for him who is perfected in Christ.

-Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, Book 1, Chapter 5

So we can draw from the good traits of the Anglo-Saxon warrior culture, something which The Wanderer evidently does. Christianity takes what is righteous in every culture, and highlights it because every good gift is from God. We reject everything evil, heinous, and reprehensible to God in every culture. We desperately need that perspective in our day in resisting Liberalism, and its critical theory, rejection of objective morals, and adoption of victim-oppressor morality scales. We need to reject the idea that “being on time” and “nuclear family” are “doing a racism.” That’s a demonic idea. As Christians, we take what’s good in every culture. It is truly ours, because:

Is He not the God of Gentiles too? Yes, of Gentiles too, since there is only one God, who will justify the circumcised by faith and the uncircumcised through that same faith.

Romans 3:29-30

God’s eternal law is above every culture, and every culture has fallen from that law in various areas. As Christians, we can unapologetically love the good in a culture and hate the evil. There are things that are “core” to a culture that are sin and need to end forever. Human sacrifice was “a central cultural expression” to most pagan cultures. That needed to be destroyed.

But, “grace restores nature”, (an idea from theologian Herman Bavink3 that my friend Jackson Stark talks about in his excellent post here4) it does not remove it. So man’s virility, strength, warrior courage, and wonder at the natural world that is expressed in the culture of The Wanderer’s pagan ancestors is only elevated by Christianization. The pagan fathers tried to feel their way toward the Unknown God, and the sons' fingers grabbed onto the wood of His Cross.

Manhood in Winter & Saxon Stoicism

No man grows wise without he have his share of winters.

This is one of the best one-liners of the poem; it encapsulates the message of the whole. No man grows wise without he have his share of winters. Outside of Eden, we gain wisdom like we gain bread: by the sweat of our brow and the discipline of God.

These winters of the Wanderer are relevant to the issues of masculinity in our day. The Wanderer has lost his political belonging by the death of his lord. He has lost close friendships with the young men that he walked and fought beside in his youth. He has lost “gold-friend” and “mead-hall”: “fallen all this joy.” Men today similarly remember the generations that came before them. The sentiment, “We were a proper country once” has come to dominate a lot of the writing about masculinity in the last few years. A general decline of trust in government and an erosion of masculine virtues and brotherhood have a lot of young men upset, and they have taken the whole bottle of red pills. But some of the pills were from an old prescription, and they had turned black.5

The Wanderer is not a young man with a bitter heart, because Heaven has given him a new heart. He is an older, wiser man. The winters have been cold, but his heart has not frozen over into an ice sculpture to Nihilism as many young men’s hearts today have done. Through hardships, we should get wisdom:

A wise man holds out; he is not too hot-hearted, nor too hasty in speech, nor too weak a warrior, not wanting in fore-thought, nor too greedy of goods, nor too glad, nor too mild, nor ever too eager to boast, ere he knows all.

As a young man, God’s primary admonition is to “be self-controlled” (Titus 2:6), which encompasses all of the virtues that the Wanderer describes. That is our duty in this station of life. The virtues expressed here are ones we need to strive to recover.

Patience: He "holds out. He is not too hot-hearted. He is not too hasty in speech. Earlier in the poem the Wanderer praises a quiet man who knows how to keep things to himself:

It is in man no mean virtue That he keep close to his heart’s chest Hold his thought-hoard, think as he may.

Strength: He is not too weak a warrior. Part of virtue is being a good steward of your health and optimizing your strength for the good of the Kingdom of God and the provision and protection of your family.

Prudence: He is not wanting in fore-thought. He thinks ahead and plans.

Contentment: He is not too greedy of goods. He knows what it is to ask for and be thankful for daily bread.

Dignity: He is not too glad, nor too mild. He knows there is a time for joy, but not to be childish and giddy. But he knows when to rejoice and enjoy the good gifts of God, and is not dower.

Humility: he does not boast, before he knows all.

Let us remember and imitate these virtues. The book of Proverbs shows us that wisdom is not the same as being clever. Wisdom is founded on the fear of the Lord and is a moral quality. Cleverness can make you a rich man, but the devil is clever. Wisdom is needed to be a righteous man.

Ubi Sunt?

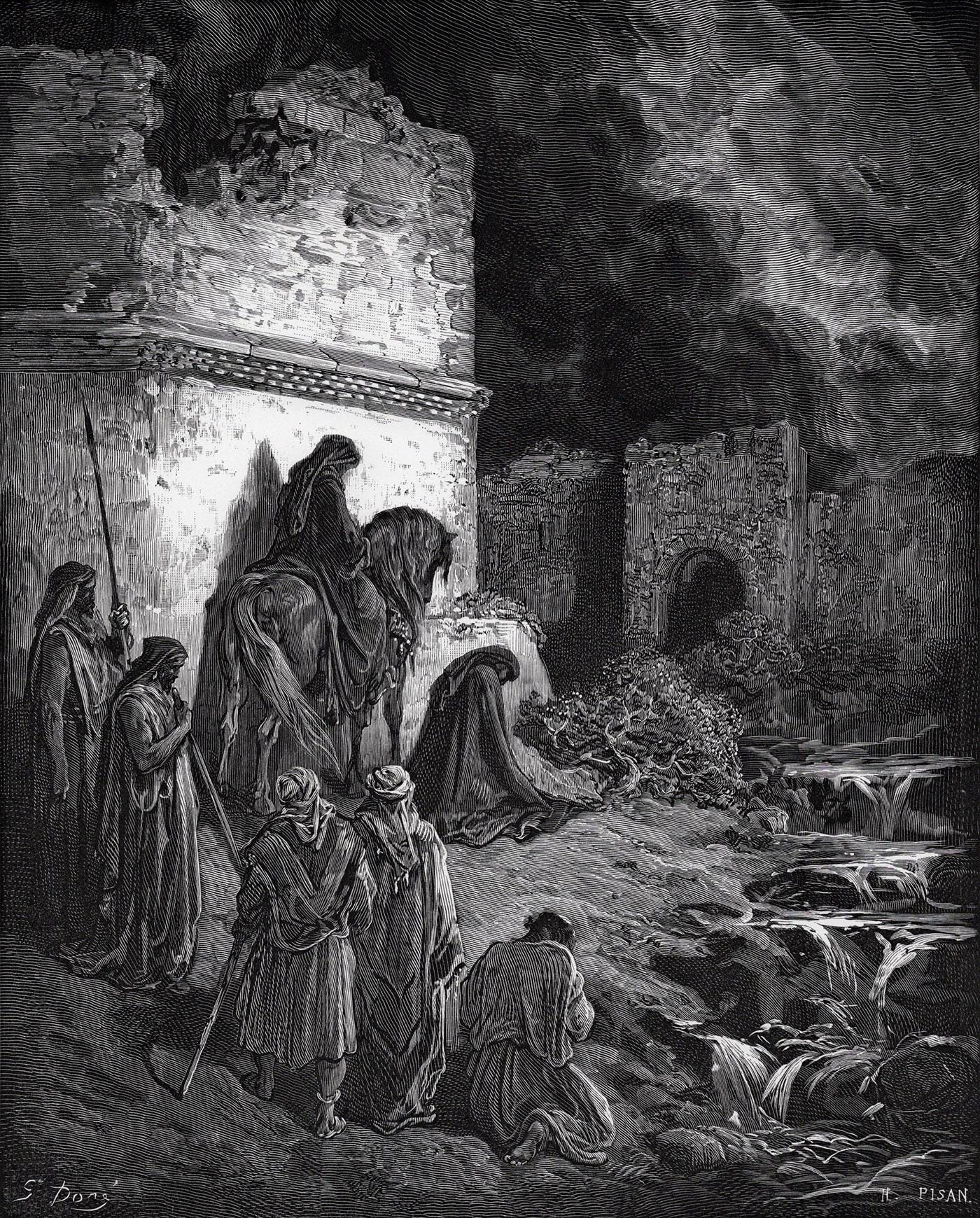

As we enter the season of Lent, we remember that we are dust. We remember that every Babel that man builds in this life will ultimately be a pile of rubble. The Wanderer expresses that idea very well. There is a Latin rhetorical question from the Vulgate, ubi sunt? meaning where are they? It became a trope in medieval poetry. It expresses the transience of life. There is an excellent ubi sunt section6 of The Wanderer:

Where is that horse now? Where are those men? Where is the hoard-sharer? Where is the house of the feast? Where is the hall's uproar? Alas, bright cup! Alas, burnished fighter! Alas, proud prince! How that time has passed, dark under night's helm, as though it never had been!

These are sentiments that every generation can express. We all see loss in this life. But we can especially sense this when we are a nation under obvious judgment from God, and can see various moral downgrades in recent memory. We can look at our universities, as

has done here, and say, where are they?These ubi sunt sentiments have a purpose, and it is not despair. We are warned in Ecclesiastes not to be those who say, “Man, those were the good old days!”

Say not, “Why were the former days better than these?” For it is not from wisdom that you ask this.

Ecclesiastes 7:10

The purpose is to remember our mortality. The purpose is to see the ruins of the institutions behind us, and confess, “The grass withers, the flower fades, but the word of God endures forever (1 Peter 1:24)” We are to look at the ruins of the walls, like Nehemiah, and begin to look for ways to rebuild.

The purpose of this remembering is not to idolize a past grandeur of human glory. Glorious creations of man only profit us insofar as they are created to the greater glory of God, and insofar as later generations receive them as blessings from God. When we forget the Giver, the gifts turn to dust.

We are to “remember also your Creator in the days of your youth, before the evil days come and the years draw near of which you will say, “I have no pleasure in them”; before the sun and the light and the moon and the stars are darkened and the clouds return after the rain… and the dust returns to the earth as it was, and the spirit returns to God who gave it” (Ecclesiastes 12).

The Wanderer ends his poem, not with further wandering, but with hope. And not generic hope: generic hope in “the goodness of humanity” or some other nonsense. It is hope in a real promise of God. It is hope that answers our greatest need:

Well is it for him who seeks forgiveness, the Heavenly Father's solace, in whom all our fastness stands.

P.S. If you enjoyed this post, please leave a comment or a like letting me know. This may become the first in a short series of posts drawing from the Exeter Book, including some other pieces that influenced specific parts of Tolkien’s LOTR. Thank you, in Christ, Cody

Pick up The Earliest English Poems to support the translation work of Michael J. Alexander.

This concept makes up a good bit of Chesterton’s Everlasting Man. I talk a bit about this a bit in my post Story is Fundamental.

“Grace restores nature and raises it to its highest fulfillment, but it does not add a new, heterogeneous component to it.” Bavink, RD III 582

See Douglas Wilson’s series of posts Dear Gavin

Tolkien, who was Professor of Old English, used some of the wording in this seciton in the Lord of the Rings, at the Lament of the Rohrim:

Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?

Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

This was brilliant.

I'm definitely among those who always do enjoy hearing about or reading obscure esoteric literature.

And that line "No man grows wise without he have his share of winters"

will be staying with me for a long time to come.

If you turned this into a series, I'd definitely read more!