Breath of God, Light of Our Lamps

A Midnight Prayer Practice in the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus

At midnight rise and wash thy hands with water and pray. And if thou hast a wife, pray ye both together. —The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus

The middle of the night is when our God called Abraham, His friend, out from his tent and showed him the stars. When Jacob wrestled. When Joseph dreamed. When the Angel of Death passed through Egypt.

This is the time Boaz noticed Ruth, David meditated on the Law, and the Apostles were freed from prisons.

The Silence of Creation

This is when creatures are asleep. Birds and trees and waters and beasts pause for a moment. In the 3rd century Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, we read:

For those very elders who gave us the tradition taught us that at this hour all creation rests for a certain moment, that all creatures may praise the Lord: stars and trees and waters stand still with one accord, and all the angelic host does service to God by praising Him, together with the souls of the righteous.1

The lesser creatures cease, giving space to the angelic hosts and souls of the righteous. They cease, and in their silence, we can hear the seraphic holy holy holy. They cease, that the Church Militant might turn the focus of her spiritual senses to the New Song, the song of Christ, that will never end.

We sometimes hear that song louder in the silence of the night watches. We let our prayer rise before the Almighty like silent incense, and the lifting of our hands as the evening sacrifice. Creation itself waits for the revealing of the sons of God.

A Midnight Prayer Practice

You may have noticed the interesting instruction to “wash your hands” at midnight prayer. Josef A. Jungmann writes in The Early Liturgy, “Obviously this is the same idea as the Lavabo—to wash the hands before undertaking something sacred.” But another “washing” is mentioned shortly after. It is a somewhat strange suggestion, but I find it to be profound:

Hippolytus instructs his readers to breathe into their hands and then sign themselves with the Sign of the Cross. For the moisture of the breath is said to come from the heart, where, since Baptism, the Holy Ghost has His dwelling.2

Here is the source quotation from the Apostolic Tradition as translated in Gregory Dix’s The Shape of the Liturgy:

By catching thy breath in thine hands and signing thyself with the moisture of thy breath, thy body is purified even unto thy feet. For the gift of the Spirit and the sprinkling of the font, drawn from the heart of the believer, purifies him who has believed.3

I find this suggestion to be powerful, and I have profited from it in my personal prayer life. Let the mind pray; let the body pray also. Let Christ be invoked and let His enemies be scattered. Let the moisture of the breath recall the Holy Spirit, Who is God, and let the Sign of the Cross recall the sacrifice of our Lord:

It is an affirmation of the adoption and illumination that we received at Baptism, and a reminder to abide in those graces.

It recalls the moment when our Lord, after His Resurrection, breathed on His Apostles, saying, “Receive the Holy Spirit.”

It recalls the Holy Spirit’s procession in spiration and love in the Godhead.

It recalls the Holy Spirit’s presence with us as Comforter. The breath recalls the wind in the upper room on the day of Pentecost. The warmth of that breath recalls the flames of fire.

It is a prayer for cleansing from any daily sins.4

The Apostolic Tradition sees such prayer as salutary, not only for the clerics and monastics but even for the married, as evidenced by the introductory quotation. With electric lights and a service economy, today we have a different sleep schedule than our brothers in the third century. Whatever our station, we are invited to redeem the time and grow in the spiritual life.

But those who have the gale of the Holy Spirit go forward even in sleep. —Practice of the Presence of God.

The Parousia

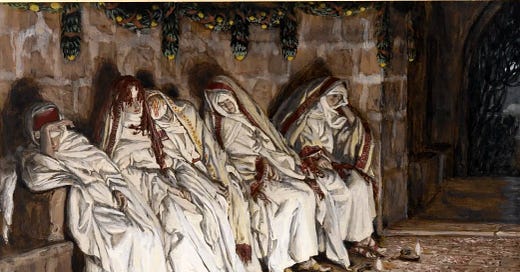

The warm breath into our hands recalls another image: Lighting, trimming, and tending a lamp. And that is the other emphasis of nighttime prayer: the Second Coming. The Parable of the Ten Virgins corresponds to this prayer practice well. If the general emphasis of midnight prayer is peace in the Holy Spirit and the silence of creation, another emphasis is on the sudden coming of Christ, Who will soon break the silence.

And at midnight there was a cry made, ‘Behold, the bridegroom cometh; go ye out to meet him.’ —Matthew 25:6

Jungmann notes this early association of the nighttime prayer offices with the Resurrection and the Second Coming.5 “The parousia [Greek, the Coming]—again the favorite theme of primitive Christian thought appears; the parousia, for which everyone must always be ready…Christ is risen and will come again.”6

In the midst of sleep, there is a repudiation of the slumber of sin. We take a moment to remember the Holy Ghost, the Comfoter, Who is the Light of our Lamps until the Bridegroom comes. Meditation on Christ’s second coming animates us to love and good works, for we know His recompense is with Him. Waking or sleeping, the Helper helps us when we do not know how to pray as we ought, that we might advance in the Way, until the Day dawns.

But you, beloved, building yourselves up in your most holy faith and praying in the Holy Spirit, keep yourselves in the love of God, waiting for the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ that leads to eternal life. —Jude 20–21

The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, translated by Burton Scott Easton. Traditionally attributed to St. Hippolytus of Rome in the third century. Some modern scholars question the attribution, but they place it no later than the fourth century.

Josef A. Jungmann S.J. The Early Liturgy, pg. 103. See this post:

Dom Gregory Dix O.S.B. The Shape of the Liturgy, 66, v. 11

Hippolytus reaffirms here the constant teaching of many Church Fathers: that daily sins into which the justified stumble are remitted and cleansed by prayer.

Others have pointed out the “patristic witness to the eschatological character of Christian prayer at night.” See Robert F. Taft, The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West: The Origins of the Divine Office, pg. 15

The Early Liturgy, pg. 103

Sweet and holy ministrations.

Beautiful reminder that prayer isn’t just words—it’s breath, body, memory, and waiting. This midnight practice feels like a secret passed through time.