Spain: the hammer of heretics, cradle of Isidore of Seville, of St. John of the Cross, of St. Dominic; evangelist of the New World, maintainer of medieval scholasticism!1 I have begun, in my walk down the great halls of Christendom, to enjoy your contributions to the Great Books. El Cid, Don Quixote, and The Ascent of Mt. Carmel have delighted and sharpened me.

But your daughter, the rest of the Hispanic world in Central and South America: where are her greats? What are her classics? I asked this question to the literary intelligentsia, and they pointed me to Gabriel García Márquez and Pablo Neruda. Two atheists, supportive of the political left (which for South American politics, is reallly left). The work that I have read of theirs has tasted like existential dread, not like transcendent beauty. I am sure there is literary skill in their work, but the worldview is false. Laboring through older books from another language is not worth it to me if the reward is the very modernism that I am trying to escape by reading old books.

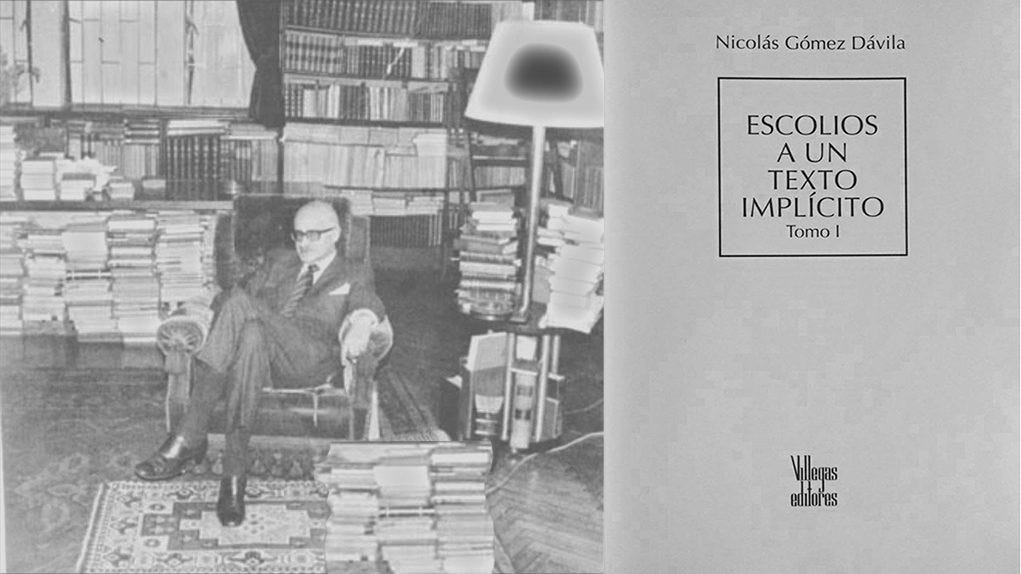

I had given up and was just going to stick to Don Quixote for the advancement of my Spanish when I came across a quote from Nicolás Gómez Dávila. I had never heard the name, but loved the quote. I searched up his name. “A classicist, a scholar, a traditionalist, born in 1913 in Bogota, Colombia?” I found myself walking to the local university library on a Saturday morning to print out one of his books.

“I’ll take a PDF printout of this book by a Colombian reactionary traditionalist aristocratic right-wing Catholic version of Márquez, please”, was not what the young lady at the front desk expected to hear. “Some call him the Nietzche of the Andes,” I tell her. She just raises her eyebrows, nods, and goes back to shuffling some papers.

I had no desire to climb inside the worldview of Márquez and Neruda. But I do want to climb inside the worldview of Nicolás Gómez Dávila. I want to do what I have done with the worldviews of Tolkien, Lewis, and Chesterton, with Pascal, Dostoevsky, and Augustine. The substance of their worldview is something valuable and unctuous, like Ishmael’s spermaceti oil. I want to draw it out, even if that means mental toil.

Tolkien from Bogotá, the Classical, the Christian

I am finding in Nicolás Gómez Dávila a sort of Colombian J.R.R. Tolkien: a classicist, and a Christian. Gómez Dávila said,

Rather than a Christian, perhaps I am a pagan who believes in Christ.

His point here is that premodern man had many true and noble assumptions about the world. When the pagan became a Christian, all the prolegomena, these accurate first principles, remained—because they were good. But the moderns have rejected, not only the Triune God, but even those underlying principles. If you grow up in this secular humanist culture, even after becoming a Christian you have a lot of assumptions to untangle.

Christianity completes paganism by adding confidence in God to fear of the divine.

So, in appreciating the pre-Christian pagan world2, Tolkien, Lewis, and Nicolás Gómez Dávila are not advocating for some return to pagan worship. They are saying that the Christian claims make a lot of sense to someone who had the assumptions of the ancient classical world. It is more of a statement about how bad it is today: they are saying that modernity’s barren godlessness is worse than the pagan’s Paganism. Paganism had a demon, but modernity is a house swept clean, with seven more powerful demons entering in.

An Indignant Medieval Peasant

South American politics appears to be very complicated, but Gómez Dávila can be classified as a reactionary to modernity. He intentionally avoided political office. He has been called an “indignant medieval peasant.” He said about his own views:

My convictions are the same as those of an old woman praying in the corner of a church.

I am enjoying getting to know a traditionalist South American mind that loves Thucydides, Don Quixote, and the Latin Rite; who didn't go to university; who taught himself classical literature, and then started a university; who wrote against Marxism and modernism with a Lewis-like “medievalist” perspective.

Reading him is like reading Márquez and Neruda if you sent them to confession, and for penance had them spit on a copy of the Communist Manifesto and recite Aquinas. Or, if you duplicated Blaise Pascal, stuck him in a Colombian panadería, and told him to stop pontificating about predestination, take a sip of aguardiente, and finish his Pensées by defeating socialism. Whichever way you look at it, Gómez Dávila is a good read.

There is a great article about his life and work here from the Imaginative Conservative3, and here4 from

.The main work that Gómez Dávila left behind is Escolios a Un Texto Implicito5, a collection of his own aphorisms (that he called escolios, ‘glosses’). But these small aphorisms are like the tips of icebergs.

If you have an intermediate level of Spanish knowledge, and enjoy the Great Books tradition in English, then you should give Nicolás Gómez Dávila in the original Spanish a shot. Here is a PDF of volume one of the Escolios:

Selected Escolios

Modern man defends nothing energetically except his right to debauchery.

It fell to the modern era to have the privilege of corrupting the humble.

When it comes to knowledge of man, there is no Christian (provided he is not a progressive Christian) whom anybody has anything to teach.

Modern man believes he lives amidst a pluralism of opinions, when what prevails today is a stifling unanimity.

The classical humanities educate because they ignore the basic postulates of the modern mind.

What concerns the Christ of the Gospels is not the economic situation of the poor man, but the moral condition of the rich man.

Something is modern if it is the product of an initial act of pride; something is modern if it seems to allow us to escape the human condition.

After experiencing what an age practically without religion consists of, Christianity is learning to write the history of paganism with respect and sympathy.

Those who replace the “letter” of Christianity with its “spirit” generally turn it into a load of socio-economic nonsense.

The root of reactionary [traditionalist] thought is not distrust of reason but distrust of the will.

Common sense is the paternal house to which philosophy returns, in cycles, feeble and emaciated.

Ages of sexual liberation reduce to a few spasmodic shouts the rich modulations of human sensuality.

It is customary to proclaim rights in order to be able to violate duties.

One who remembers the smells of grass trampled under his bare feet never breathes well among buildings.

We will soon reach the point where civilization declines with each additional comfort.

The left does not condemn violence until it hears it pounding on its door.

Man’s moment of greatest lucidity is when he doubts his doubt.

The purpose of sex education is to make it easier to learn sexual perversions.

Europe, properly speaking, consists of those countries educated by feudalism.

To be Christian, in accordance with the latest fashion, consists less in repenting of our sins than in repenting of our Christianity.

When he repudiates [liturgical] rites, man reduces himself to an animal that copulates and eats.

Faith is not assent to concepts, but a sudden splendor that knocks us down.

There is no spiritual victory which need not be won anew each day.

An atheist is respectable as long as he does not teach that the dignity of man is the basis of ethics and that love for humanity is the true religion.

The true religion is monastic, ascetic, authoritarian, hierarchical.

The Gospels and the Communist Manifesto are on the wane; the world’s future lies in the power of Coca-Cola and pornography.

The Church’s function is not to adapt Christianity to the world, nor even to adapt the world to Christianity; her function is to maintain a counterworld in the world.

Every end other than God dishonors us.

Thank you for reading this post. If you found this interesting, let me know in the comments, and consider sharing it. Nicolás Gómez Dávila is criminally unknown to the English world, and he can raise the standard of Spanish literature.

This is a play on a quote from Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo: “Spain, evangelizer of the middle of the world; Spain hammer of heretics, light of Trent, sword of Rome, cradle of Saint Ignatius; that is our greatness and our unity; we have no other."

Read more about this in my series on the Exeter Book, and the influence of pagan thought on the converted Anglo Saxons. Specifically, my post on The Wanderer.

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2019/07/nicolas-gomez-davila-nietzsche-andes-nayeli-riano.html

There is not a book at the moment to my knowledge that translates Escolios a Un Texto Implicito in its entirety into English. The blog https://don-colacho.blogspot.com/ has done an excellent job of doing that translation though. Thanks to

for showing me the blog.

Thank you for bringing this to my attention; I really enjoyed these aphorisms. I am excited to learn more about the man.

I've never read Dávila, I appreciate the tip. I've taught both El Cid and Don Quixote in my Spanish lit classes, they need to be held in higher esteem by anglophones.

As far as recommendations, you've been talking to the wrong people! (Although Neruda does delight me.) You want Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Octavio Paz. Especially Borges, if you love Tolkien.